Medellín-Sánchez et al., 2025 de

Research article

Phytoextraction of lead (Pb) by Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (Poaceae).

Medellín-Sánchez Marianel1, Diaz-Torres Rocío del Carmen1, Carranza-Álvarez Candy 1, Maldonado-Miranda Juan José 1, Montes-Rocha José Angel 1

1Facultad de Estudios Profesionales Zona Huasteca, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Ciudad Valles, San Luis Potosí, México.

Correspondencia: angel.montes@uaslp.mx

Área Temática: Ciencias Ambientales Recibido: 03 septiembre 2025 Aceptado: 18 noviembre 2025 Publicado: 31 enero 2026

Cita: Medellín-Sánchez M, Díaz-Torres RC, Carranza-Álvarez C, Maldonado-Miranda JJ and Montes-Rocha JA. 2025Phytoextraction of lead (Pb) by Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud (Poaceae). Bioc Scientia 2(1). https://doi.org/10.63622/RBS.2517 Copyright: © 2024 by the authors. Submitted for possible open access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). |

Resumen: La contaminación por metales pesados, en particular por plomo (Pb), es uno de los principales desafíos ambientales a nivel mundial. El Pb se detecta con frecuencia en cuerpos de agua superficiales y sedimentos, y su exposición puede causar una variedad de efectos adversos para la salud en plantas, animales y humanos. Por lo tanto, el desarrollo de tecnologías sostenibles y rentables para reducir el Pb en sistemas acuáticos es de vital importancia. La fitorremediación con Phragmites australis es una estrategia de remediación prometedora. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar el potencial de fitoextracción de P. australis para la eliminación de Pb. Se probaron dos condiciones experimentales: agua de río natural (PbNW) y agua desionizada (PbDW), ambas adicionadas con 250 mg/L de Pb(NO₃)₂. Se cuantificó Pb en tejidos vegetales aéreos y subterráneos. En los tejidos aéreos, las concentraciones de Pb alcanzaron 26.4 ± 1.3 mg/kg (PbDW) y 1.5 ± 0.2 mg/kg (PbNW), mientras que, en los tejidos subterráneos, las concentraciones fueron de 103.4 ± 11.5 mg/kg (PbDW) y 38.9 ± 10.3 mg/kg (PbNW). Según el factor de translocación (FT) y el factor de bioconcentración (FBC), el Pb se acumuló predominantemente en los tejidos subterráneos. Además, se observó un ligero aumento de la conductividad eléctrica (DW: 0.2 a 0.6; PbDW: 0.2 a 0.6; PbNW: 0.3 a 0.6 mS/cm). Las concentraciones de Pb en solución disminuyeron durante el experimento, de 227.4 a 170.1 mg/L en PbDW y 83.95 a 4.6 mg/L en PbNW, lo que confirma el potencial de la planta para la eliminación de Pb. P. australis demostró una capacidad importante de acumulación de Pb principalmente en raíces y rizomas y se clasificó como una especie fitoestabilizadora. Características que la hacen una especie adecuada para la restauración de sitios impactados por Pb.

Palabras clave: Contaminación hídrica, plomo, fitorremediación, Phragmites australis.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Abstract: Heavy metal pollution, particularly from lead (Pb), remains one of the major environmental challenges facing society worldwide. Pb is frequently detected in surface water bodies and sediments, and its exposure can cause a range of adverse health effects in plants, animals, and humans. Therefore, the development of sustainable and cost-effective technologies to reduce Pb concentrations in aquatic systems is critically important. Phytoremediation using Phragmites australis has emerged as a promising remediation strategy. This study aimed to evaluate the phytoextraction potential of P. australis for Pb removal. Two experimental conditions were tested: natural river water (PbNW) and deionized water (PbDW), both amended with 250 mg/L of Pb (NO₃)₂. Pb accumulation was quantified in both aerial and underground plant tissues. In aerial tissues, Pb concentrations reached 26.4 ± 1.3 mg/kg (PbDW) and 1.5 ± 0.2 mg/kg (PbNW), while in underground tissues, concentrations were 103.4 ± 11.5 mg/kg (PbDW) and 38.9 ± 10.3 mg/kg (PbNW). Based on the translocation factor (TF) and bioconcentration factor (BCF), Pb was found to accumulate predominantly in underground tissues. Additionally, a slight increase in electrical conductivity (DW: 0.2 to 0.6; PbDW: 0.2 to 0.6; PbNW: 0.3 to 0.6 mS/cm) was observed. Pb concentrations in solution decreased during the experiment, from 227.4 to 170.1 mg/L in PbDW and from 83.95 to 4.6 mg/L in PbNW, confirming the plant's potential for Pb removal. P. australis demonstrated a significant capacity to accumulate Pb, mainly in roots and rhizomes, and was classified as a phytostabilizing species. These characteristics make it a suitable species for the restoration of sites impacted by Pb.

Keywords: water pollution, lead, phytoremediation, Phragmites australis.

INTRODUCTION

Water quality is one of the main ecological and health problems today, due to the contribution of heavy metal ions derived from industrial activities, mining, electroplating, and battery manufacturing (Hossain et al., 2022). Heavy metals are elements that are classified as extremely toxic. Pb is a heavy metal identified in various environmental matrices such as rivers and lakes. One of the main concerns about heavy elements such as Pb is that they do not degrade and accumulate over time (Hasan et al., 2023). Pb is an extremely toxic metal that originates from anthropogenic activities such as the use of Pb-based paints, mobile batteries, and gasoline. (Das et al., 2023). Pb can react in air and water with various elements to form sulfates, carbonates, and lead oxides. In the atmosphere, it can be eliminated by rain, transferring it to the ground and bodies of water. In the soil, Pb binds strongly to particles such as clay, which are washed away by rain into water bodies (Collin et al., 2022). Lead in a body of water can enter the food chain by accumulating in the bodies of lower organisms, which are then consumed, causing lead to enter the human body. Exposure to lead causes various health effects, including dizziness, insomnia, memory loss, damage to brain function in babies and children, and impaired perception, language, and memory (Song et al., 2025). Proposing technologies that help reduce Pb concentrations in water bodies is vitally important.

Conventional techniques such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, and electrochemical removal have several disadvantages, including high energy requirements, toxic sludge production, incomplete removal, high technical requirements, and high installation, operation, and maintenance costs. Methods such as biological ones are economically viable and do not generate secondary pollution, offering practical and sustainable solutions such as phytoremediation (Damilola et al., 2019; Zamora-Ledezma et al., 2021). Among these, bioremediation has gained considerable attention due to its environmentally friendly nature and compatibility with sustainable and climate-smart agricultural practices for managing pollutants across various environmental matrices. This technique relies on the use of biological agents such as bacteria, fungi, and plants (Das et al., 2023).

A key branch of bioremediation is phytoremediation, an ecological, promising, and cost-effective strategy that employs plants to remediate contaminated environments. Phytoremediation encompasses several mechanisms, including the translocation, transport, transformation, accumulation, and in some cases, volatilization of contaminants (Kafle et al., 2022).

Phytoremediation is mainly used to reduce the damage caused by heavy metals to the environment and human health with minimal negative impact on the environment (Shen et al., 2022). P. australis is a plant commonly used in the phytoremediation of water, soil, and sediment at sites impacted by heavy metals (Rezania et al., 2019; Chitimus et al., 2023). P. australis is widely used because it is a perennial plant, has a wide geographical range, inhabits both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, is a cosmopolitan species, and is distributed in temperate and tropical regions (Perna et al., 2023). This plant species is known for providing habitat and food for both aquatic and terrestrial organisms, contributing to ecosystem stability by preventing soil erosion. Additionally, its physiological and morphological characteristics have demonstrated high potential as a biological filter for mitigating environmental pollution (Mike et al., 2020). P. autralis has the capacity for translocation, resistance to toxicity, and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the following order: roots > shoots > leaves, making it a suitable species for the phytostabilization of heavy metals (Klink, 2017; Rezania et al., 2019).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the phytoextraction capacity of P. australis for lead (Pb) in two different water matrices: surface water from the Valles River in Ciudad Valles, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, and deionized water under controlled laboratory conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling of surface water and plant material

Water and plant samples were collected from the Valles River, Cd. Valles, S.L.P. (22°01'18.3“N, 99°03'04.0” W). Three liters of surface water were collected using plastic containers previously washed with 10% nitric acid. For plant sampling, 27 P. australis plants between 15 and 25 cm in height, with developed roots, rhizomes, stems, and leaves, were collected from the ground. They were then transported to the laboratory in a portable cooler to maintain sample integrity.

Assay

Three treatments were carried out in the laboratory: in treatment DW 1 L of deionized water was added to a beaker containing three plants. In treatment PbDW, 1 L of deionized water was added to a beaker containing 250 mg of Pb(NO3)2, and then three plants were added. In treatment PbNW, 1 L of surface water (Valles River) was added to a beaker, containing 250 mg of Pb(NO3)2 and three plants. The entire test was performed in triplicate. A review was conducted to determine the concentration used in this study. Several tests were carried out (500, 400, and 300mg/L), and in each case, the plant died before 9 days until it was identified that at 250, the plant resisted the 9-day period (Bello et al., 2018; Bernardini et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018).

Determination of physicochemical properties: pH and electrical conductivity (EC)

The pH and EC were determined daily during the 9 days of exposure, starting on day 0 (without adding Pb and plant to the solutions). A waterproof probe was used to quantify the pH and EC, which was calibrated daily with certified standards. The results obtained were recorded during the exposure time for each treatment (DW, PbDW, PbNW) and were performed in triplicate (Montes-Rocha et al., 2024).

Determination of Pb in surface water and plant material

Water treatment

For each of the treatments (DW, PbDW, PbNW), three 10 mL samples were taken over a period of nine days, yielding a total of 90 samples, which were immediately acidified with 3% nitric acid. Subsequently, digestion was performed in a LabTech autoclave (121°C/30 min). Once digestion was complete, the samples were stored in 15 mL conical tubes at 4°C until use (Montes-Rocha et al., 2024).

Treatment of plant material

After 9 days of exposure to Pb in the DW, PbDW, and PbNW treatments, the plants were removed and sectioned into aerial tissue: stem and leaf (AT) and underground tissue: root and rhizome (UT). They were then placed in an oven (Lindberg/BlueM) for 5 days at 70 °C. After 5 days, the dry material was ground to a powder smaller than 2 microns in an analytical mill (IKA® WERKE). Cold digestion was then performed by adding 50 mg of plant material (AT and UT) and 3.5 mL of nitric acid (HNO3) in 10 mL polyethylene flasks. The mixture was left to stand for 5 days, after which 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added. Finally, the mixture was made up to 10 mL with deionized water and stored at 4 °C until use (Montes-Rocha et al., 2024).

Determination de Pb(NO3)2

The digested samples of water and plant material (AT and UT) from the DW, PbDW, and PbNW treatments were acclimatized to room temperature for the determination of Pb(NO3)2. Pb was determined using a flame spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, iCE 3000 SERIES AA Spectrometer). For quality control, a calibration curve was performed with certified Pb standards, and enriched standards were also used (Standard Reference Material 1643f, 97% recovery) (Montes-Rocha et al., 2024).

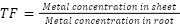

Translocation factor (TF)

TF was determined for the PbDW and PbNW treatments. Result >1 means that the plant accumulates in aerial parts, and a result <1 means that the plant accumulates in underground parts. The index was calculated using the following formula (Rai, 2021):

Bioconcentration factor (BCF)

The BCF was determined for the aerial and underground parts; a bioconcentration factor >1 indicates that the plant is efficient removing metals (Cicero-Fernández et al., 2017). The BCF was determined using the following formula:

Where CP is the concentration of the metal in the plant (root, stem, or leaf) and CS refers to the concentration of the metal in water.

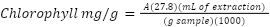

Determination of chlorophyll (Chl)

Chl quantification was performed on days 0, 5, and 9 of the trial. P. australis leaves (100 mg) were collected, then placed in a mortar with 8 mL of acetone (CH3CH3, CTR Scientific) and subsequently macerated until a homogeneous extract was obtained. This process was carried out in a dark and cold environment. The extract was filtered and placed in a 15 mL conical tube previously covered with aluminum foil to prevent exposure to light and was immediately diluted to 10 mL with deionized water. The absorbance was measured using UV-Visible spectrometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific Aquamate Plus UV-Vis, Wisconsin, USA) at a wavelength of 652 nm, using acetone as a blank. The chlorophyll content was determined using the following formula (Montes-Rocha et al., 2024):

Where A: absorbance of the sample, 27.8: absorption coefficient, 1000: dilution factor, mL extraction: milliliters of acetone extraction, g sample: weight of sample used.

Statistical analysis

The results and graphs show the mean ± standard error for pH, EC, Pb in solution, Pb in tissues, TF, BFC and Chl. An ANOVA analysis was performed with Tukey's post hoc test, with a significance level of 5%, to verify significant differences between the DW, PbDW, and PbNW treatments for pH, EC, and Chl. Student’s t-test was performed with a significance level of 5%. This analysis was conducted to compare Pb in solution between the PbDW and PbNW treatments and to compare Pb accumulation in aerial and underground tissue, TF and BCF, for each treatment (PbDW and PbNW). Pearson correlation analysis was performed between pH, EC, and Pb in solution to determine any relationship between these variables. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism statistical software, version 8.0.2.

RESULTS

pH, EC and Pb in solution

During the test, the pH behavior was recorded for each treatment, and it was observed that the DW treatment had an average pH of 6.7±0.02, the PbDW treatment had a pH of 6.1±0.1, and the PbNW treatment had a pH of 6.7±0.08. In the DW (Day 0: 6.6, Day 9: 6.8), PbDW (Day 0: 5.7, Day 9: 7.2), and PbNW (Day 0: 6.2, Day 9: 7.1) treatments, a slight increase in pH was observed as the exposure time progressed. Statistical analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between the DW and PbNW treatments (p<0.05), while the PbDW treatment showed a significant difference compared to the DW and PbNW treatments (p<0.05) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. (a) pH in solution for the DW, PbDW and PbNW treatments. (b) EC in solution for the DW, PbDW and PbNW treatments. And (c) Pb in solution for the DW, PbDW, and PbNW treatments.

The EC recorded a value of 0.5±0.04 mS for the DW treatment, 0.5±0.043 mS for the PbDW treatment, and 0.5±0.03 mS for the PbNW treatment. The EC did not show significant differences between treatments according to statistical analysis (p<0.05). However, a slight increase in EC was observed in the DW treatment (Day 0: 0.2, Day 9: 0.6 mS), PbDW (Day 0: 0.2, Day 9: 0.6 mS), and PbNW (Day 0: 0.3, Day 9: 0.6 mS). Both treatments showed significant differences (p<0.05) (Figure 1b). In the PbDW treatment, P. australis removed 57.3 mg/L of Pb from the solution, with removal remaining consistent throughout the 9 days. In the PbNW treatment, P. australis removed 83.8 mg/L from the solution, but this treatment was characterized by inconsistency, with more Pb being absorbed on some days and less on others. The PbNW treatment was the one in which the plant performed the best removal of Pb from the solution (Figure 1c). The correlation analysis showed that in the PbDW treatment, pH correlated negatively with Pb in solution (-0.295), and in the PbNW treatment, EC correlated positively with pH (0.266) and negatively with Pb in solution (-0.116).

Pb in aerial and underground tissue and indices in P. australis

Once the exposure time (9 days) to Pb had elapsed, it was found that in the PbDW treatment, the aerial tissue accumulated 26.4±1.3 mg/kg and the underground tissue accumulated 103.4±11.5 mg/kg. In the PbNW treatment, the aerial tissue accumulated 1.5±0.2 mg/kg and the underground tissue accumulated 38.9±10.3 mg/kg. Both treatments showed a significant difference between aerial and underground tissue (p<0.05) (Figure 2a). The translocation factor was 0.25±0.02 for the PbDW treatment and 0.04±0.01 for the PbNW treatment (Figure 2b). The bioconcentration factor, the PbDW treatment in the aerial tissue was 0.1±0.005 and 0.4±0.05 for underground tissue. In the case of the PbNW treatment, the aerial tissue showed a value of 0.01±0.001 and the underground tissue showed a value of 0.4±0.04 (Figure 2 c).

Figure 2. (a) Pb in P. australis aerial and underground tissue. (b) Translocation factor in PbDW and PbNW treatments. (c) Bioconcentration factor in aerial tissue (AT) and underground tissue by treatment (UT).

Chlorophyll in P. australis

PbDW treatment showed a decrease in Chl as the days of the trial progressed. On day 0, a 1. 8 ± 0.001 mg/g was recorded, on day 5 a 1.0 ± 0.1 mg/g was recorded, and finally, on day 9, a 0.8 ± 0.1 mg/g of Chl was recorded. According to the statistical analysis, day 0 showed significant differences compared to days 5 and 9 (p<0.05), indicating that on days 5 and 9 a significant decrease in chlorophyll was identified compared to day 0. In the PbNW treatment, a decrease in Chl was observed as the trial progressed. On day 0, the concentration was 2.0 ± 0.04 mg/g, on day 5 it was 1.9 ± 0.1 mg/g, and finally on day 9 it was 0.6 ± 0.01 mg/g. Statistical analysis showed that days 0 and 5 did not present significant differences, and a significant decrease in chlorophyll was observed until day 9 (p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chl content in P. australis aerial tissue exposed to PbDW and PbNW treatments.

DISCUSSION

Throughout the experiment, P. australis showed tolerance to a concentration of 250 mg/L of Pb(NO₃)₂ in both PbDW and PbNW treatments. The physicochemical properties of natural river water appear to influence the effectiveness of phytoextraction, particularly by affecting the chemical speciation and solubility of Pb in solution. When Pb(NO₃)₂ was added to river water, visible precipitation occurred, probably due to the presence of inorganic salts such as sulfates, carbonates, and chlorides, which can form insoluble Pb compounds. An increase in pH was observed in all treatments, which can be attributed to the presence of P. australis, which has the ability to release root exudates such as organic acids (malate, citrate, oxalate) that modify the pH in the rhizosphere environment. pH modification is one of the plant's adaptation mechanisms and consists of pH regulation through metabolic processes such as H⁺ ion exchange, a key function of root cells that promotes plant development under stressful conditions, such as nutrient deficiency and metal toxicity (Ding and Sun, 2021).

Maintaining an elevated pH in the rhizosphere is beneficial for nutrient availability and overall plant health. Correlation analysis indicated a negative relationship between pH and Pb concentration in the solution: as pH increased, the concentration of dissolved Pb decreased. This trend is consistent with the well-established influence of pH on metal solubility and bioavailability. Higher pH conditions favor Pb precipitation or adsorption onto particles, thereby reducing its mobility and availability in solution for plant uptake.

These results agree with those reported by Álvares-Robles et al. (2022), who observed a moderate increase in interstitial water pH from 5.6 ± 0.09 to 7.1 ± 0.06 accompanied by a reduction in Pb concentration from 0.03 ± 0.00 to 0.01 ± 0.00 mg/L in a study involving P. australis growing in trace element-contaminated soils. Similarly, Guzmán et al. (2022) conducted a laboratory experiment using constructed wetlands treated with PbSO₄, reporting a decrease in pH (from 10.59 to 8.30), a slight increase in electrical conductivity (from 1.06 to 1.42 µS/cm), and a 20% reduction in Pb concentration in solution (from 0.46 to 0.37 mg/L).

Collectively, these results support the conclusion that although P. australis exhibits relatively low Pb uptake efficiency, its capacity to reduce Pb concentrations in water through mechanisms such as precipitation, adsorption, and rhizosphere modification positions it as a viable option for the treatment of heavy metal-contaminated aquatic environments. The underground tissue represents the first barrier that is in direct contact with metals, and the aerial tissue is not in contact with metals. However, there are various mechanisms that help mobilize metals to the aerial parts (Mike et al., 2020). P. australis showed an adequate capacity to extract Pb from the solution, with the underground tissue being the main organ where it accumulated in both the PbDW and PbNW treatments. Subsequently, Pb accumulation occurred in the aerial tissue in both treatments (PbDW and PbNW). Several authors agree with the results obtained in this study. Bragato et al., (2009), they conducted a study beginning in December 2002 in an experimental wetland in northern Italy. They mention that P. australis has a wide capacity to accumulate metals (Cu, Zn, Ni, and Cr) over the course of a year, mainly in the roots and rhizomes, followed by the stem and leaves. Another study is that of Hamidian et al. (2014), which was conducted in Iran, where plant samples were collected in wastewater areas of a gas refinery. They observed that P. australis has the ability to accumulate Pb (1.78-9.38 µg/g) in tissues, mainly in the root and rhizomes. Another study was conducted by Bello et al. (2018) in Saudi Arabia using a hydroponic system in which they added 5 mg/L of Pb (PbCl2) in 1 L of water to the plants (P. australis). They found that the highest accumulation of metals occurred in the roots and that as the days of exposure increased, the concentration of metals in the plant also increased. The concentration found before the experiment for Pb was 0.15 mg/g, and at the end, it was 5.21 mg/g. The TF in the PbDW and PbNW treatments yielded a value <1, indicating that the plant accumulates mainly in underground tissue and that the mechanism it uses is phytomobilization. The BCF in the PbDW and PbNW treatments in underground tissue was 0.4 and 0.4, respectively. This value is high compared to that obtained in aerial tissue (0.1 and 0.01), indicating that P. australis has a low efficiency for accumulating Pb in underground tissue in both treatments. Authors such as Hernández-Pérez et al. (2021) conducted an experiment in artificially constructed wetlands where they exposed P. australis to concentrations of 494-1853 mg/kg of Pb, obtained a TF <1 in P. australis for Pb, and recommended it for phytomobilization. They also obtained a BCF factor <1, which led them to classify P. australis as a poor accumulator. Sellal et al. (2019) exposed P. australis to 500 mg/kg of Pb and observed that it accumulates mainly in the following order: roots > stems > leaves. They classified P. australis as phytostabilizing based on the BCF (1.21) and TF (0.05). Plants such as P. australis have been shown to have the ability to secrete organic acids (malate, citrate, oxalate), dissolved organic matter, and phytosiderophores, which are essential for the solubility, transport, and absorption of metals by plants (Ding et al., 2014; Sellal et al., 2019; Montes-Rocha et al., 2024). In addition, it has functional groups on the root surface (carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino) to which metals and transporters bind, helping to mobilize metals toward the root (Zhou et al., 2025).

Heavy metals such as Pb tend to have a toxic effect and can cause alterations in membrane function, photosynthetic transport, and mitochondrial electron transport, and can alter enzymes involved in the regulation of basic metabolism (Mike et al., 2020). In the case of Chl, it was observed that as Pb exposure in the plant progressed, Chl decreased, suggesting that Pb has a negative effect on plant physiology. Metals such as Pb can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can have negative effects on plant development (Kovačević et al., 2020). P. australis possesses various enzymatic and non-enzymatic defense mechanisms (catalase, peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, proline) that can help reduce oxidative stress caused by the presence of heavy metals. Antioxidant activities such as catalase, peroxidase, and polyphenol oxidase can neutralize or eliminate free radicals derived from exposure to heavy metals. Proline can act as a chelator and eliminate singlet oxygen, as well as hydroxyl radicals, reducing the damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thus protecting photosynthetic pigments during flowering (Khalilzadeh et al., 2022). Various trials have been conducted with results similar to this trial, such as that carried out by Bragato et al., (2009), who state that over the course of a year, P. australis was exposed to heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Ni, and Cr), observing that Chl a and b decreased due to metal-induced stress conditions. Another study was conducted by Ayeni et al. (2012), in which they determined the concentration of Chl in P. australis from four sites along the banks of the Diep River in South Africa. They found that the plant was exposed to metals (Pb, Cd, Ni, Cr, and Zn) They associated the decrease in Chl a and b (7.9 and 8.8 mg/L) with the increase in heavy metals in this area. Another study with similar results to this trial was conducted by Zhang et al. (2018), they conducted a study in China, where they planted P. australis seeds in plastic containers with 20 cm of soil under greenhouse conditions and added known concentrations (0, 500, 1500, and 4500 mg/kg) of Pb (NO3)2. The authors mention that there is a reduction in photosynthetic capacity at high levels of Pb (Pb, 3000 mg/kg). The results of the previous authors agree with those presented in this trial: Chl activity decreases in the presence of Pb. Currently, P. australis has been used as a suitable species for phytoremediation in studies conducted mainly in constructed wetlands, which conclude that it is a plant with great potential for the restoration of sites impacted by heavy metals. In the study conducted by Amabilis-Sosa et al. (2016), they evaluated the accumulation of mercury (Hg) in P. australis used as a biological barrier in artificial wetlands (AW) in synthetic wastewater treatment. They introduced 33.94 mg of mercury, of which P. australis accumulated 11.14 mg±1.01 mg and 9.08 mg±0.92 mg, removing 73% to 66% of the total mercury. The study conducted by Huang et al. (2017) evaluated the capacity of P. australis to accumulate heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cr separately) in an artificial wetland. it was recorded that the rhizome had greater accumulation in summer (24.54 mg·kg−1 dry mass) and in the root during winter (13.72 mg·kg−1 dry mass). This shows that the bioaccumulation of Pb in the roots is a strategy whereby the plant can restrict the distribution of heavy metals to aerial tissues.

CONCLUSION

Phragmites australis demonstrated a notable capacity to remove lead from water bodies impacted by anthropogenic activities. The species functions as a Pb accumulator, with preferential accumulation in underground organs (roots and rhizomes), followed by lower accumulation in aerial parts (stems and leaves), classifying it primarily as a phytostabilizing plant. Environmental factors such as pH and electrical conductivity were shown to influence its phytoextraction performance. Furthermore, P. australis exhibited significant tolerance to elevated Pb concentrations, suggesting the presence of physiological defense mechanisms that mitigate metal toxicity and delay chlorophyll degradation. Based on these findings, the use of P. australis is recommended as a viable strategy for the phytoremediation of Pb-contaminated aquatic environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.M.R., R.d.C.D.T., and C.C.A; methodology, J.A.M.-R., M.M.S; software, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T; validation, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., M.M.S, J.J.M.M. and C. C. A; formal analysis, J.A.M.-R. and R.d.C.D.-T.; investigation, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.-T., C. C. A., J.J.M.M. and M. M. S; resources, C.C.-Á. and J.A.M.R.; data curation, J.A.M.-R. and M.M.S; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., C.C.A., J.J.M.M. and M.M.S; writing—review and editing, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., J.J.M.M. and C.C.A; visualization, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., J.J.M.M. and C.C.A; supervision, J.A.R.M; project administration, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., J.J.M.M. and C.C.A; funding acquisition, J.A.M.-R., R.d.C.D.T., J.J.M.M. and C.C.A; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no funding from any public or private organization.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Environmental Sciences Laboratory of the Huasteca Zone Faculty of Professional Studies (FEPZH), UASLP, for providing its facilities for the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Amabilis-Sosa, Leonel Ernesto, Siebe, Christina, Moeller-Chávez, Gabriela, & Durán-Domínguez-de-Bazúa, María del Carmen. (2016). Remoción de mercurio por Phragmites australis empleada como barrera biológica en humedales artificiales inoculados con cepas tolerantes a metales pesados. Revista internacional de contaminación ambiental, 32(1), 47-53. Recuperado en 22 de octubre de 2025, de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-49992016000100047&lng=es&tlng=es.

Ayeni, O., Ndakidemi, P., Snyman, R., & Odendaal, J. 2012. Assessment of Metal Concentrations, Chlorophyll Content and Photosynthesis in Phragmites australis along the Lower Diep River, CapeTown, South Africa. Energy and Environment Research, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.5539/eer.v2n1p128

Álvarez-Robles, M.J., Bernal, M.P. & Clemente, R. 2022. Differential response of Oryza sativa L. and Phragmites australis L. plants in trace elements contaminated soils under flooded and unflooded conditions. Environ Geochem Health, 44, 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-021-00979-y

Bello, A. O., Tawabini, B. S., Khalil, A. B., Boland, C. R., & Saleh, T. A. 2018. Phytoremediation of cadmium-, lead- and nickel-contaminated water by Phragmites australis in hydroponic systems. Ecological Engineering, 120, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.05.035

Bernardini, A., Salvatori, E., Guerrini, V., Fusaro, L., Canepari, S., & Manes, F. (2016). Effects of high Zn and Pb concentrations on Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex. Steudel: Photosynthetic performance and metal accumulation capacity under controlled conditions. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 18(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2015.1058327

Bragato, C., Schiavon, M., Polese, R., Ertani, A., Pittarello, M., & Malagoli, M. 2009. Seasonal variations of Cu, Zn, Ni and Cr concentration in Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin ex steudel in a constructed wetland of North Italy. Desalination, 246(1–3), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.02.036

Cicero-Fernández, D., Peña-Fernández, M., Expósito-Camargo, J. A., Antizar-Ladislao, B. 2017. Long-term (two annual cycles) phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated estuarine sediments by Phragmites australis. New Biotechnol, 38, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2016.07.011.

Chitimus, D., Nedeff, V., Mosnegutu, E., Barsan, N., Irimia, O., & Nedeff, F. 2023. Studies on the Accumulation, Translocation, and Enrichment Capacity of Soils and the Plant Species Phragmites australis (Common Reed) with Heavy Metals. Sustainability, 15(11), 8729. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118729

Collin, M. S., Venkatraman, S. K., Vijayakumar, N., Kanimozhi, V., Arbaaz, S. M., Stacey, R. G. S., Anusha, J., Choudhary, R., Lvov, V., Tovar, G. I., Senatov, F., Koppala, S., & Swamiappan, S. 2022. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. In Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances (Vol. 7). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100094

Damilola, A., Popoola, O., Asaolu, S., & Adebawore, A. (2019). Adsorption and Conventional Technologies for Environmental Remediation and Decontamination of Heavy Metals: An Overview. www.ijrrjournal.com

Das, S., Sultana K, W., Ndhlala, A. R., Mondal, M., Chandra, I. 2023. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Its Impact on Health: Exploring Green Technology for Remediation. Environmental Health Insigh, 17. https://doi:10.1177/11786302231201259

Ding, Y. Z., Song, Z. G., Feng, R. W., Guo, J. K. 2014. Interaction of organic acids and pH on multi heavy metal extraction from alkaline and acid mine soils. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 11(1):33–42. https://doi:10.1007/ s13762-013-0433-7.

Ding, Z., & Sun, Q. 2021. Effects of flooding depth on metal(loid) absorption and physiological characteristics of Phragmites australis in acid mine drainage phytoremediation. Environmental Technology and Innovation, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101512

Guzman, M., Romero Arribasplata, M. B., Flores Obispo, M. I., & Bravo Thais, S. C. 2022. Removal of heavy metals using a wetland batch system with carrizo (Phragmites australis (cav.) trin. ex steud.): A laboratory assessment. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 42(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2021.08.001

Hamidian, A. H., Atashgahi, M., & Khorasani, N. 2014. Phytoremediation of heavy metals (Cd, Pb and V) in gas refinery wastewater using common reed (Phragmitis australis). International Journal of Aquatic Biology, 2(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijab.v2i1.21

Hasan, Md. M., Salman, Md. S., Hasan, Md. N., Rehan, A. I., Awual, M. E., Rasee, A. I., Waliullah, R. M., Hossain, M. S., Kubra, K. T., Sheikh, Md. C., Khaleque, Md. A., Marwani, H. M., Islam, A., & Awual, Md. R. 2023. Facial conjugate adsorbent for sustainable Pb(II) ion monitoring and removal from contaminated water. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 673, 131794. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.131794

Hernández-Pérez, C., Martínez-Sánchez, M. J., García-Lorenzo, M. L. 2021. Phytoremediation of potentially toxic elements using constructed wetlands in coastal areas with a mining influence. Environ Geochem Health 43, 1385–1400 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-021-00843-z

Hossain, Md. T., Khandaker, S., Bashar, M. M., Islam, A., Ahmed, M., Akter, R., Alsukaibi, A. K. D., Hasan, Md. M., Alshammari, H. M., Kuba, T., & Awual, Md. R. 2022. Simultaneous toxic Cd(II) and Pb(II) encapsulation from contaminated water using Mg/Al-LDH composite materials. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 368, 120810. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120810

Huang X, Zhao F, Yu G, Song C, Geng Z, Zhuang P. Removal of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cr from Yangtze Estuary Using the Phragmites australis Artificial Floating Wetlands. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6201048. https://doi.org/https://10.1155/2017/6201048.

Kafle, A., Timilsina, A., Gautam, A., Adhikari, K., Bhattarai, A., & Aryal, N. 2022. Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. In Environmental Advances (Vol. 8). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2022.100203

Khalilzadeh, R., Pirzad, A., Sepehr, E., Anwar, S., & Khan, S. 2022. Physiological and biochemical responses of Phragmites australis to wastewater for different time duration. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 44(12), 130.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-022-03469-5

Klink, A. (2017). A comparison of trace metal bioaccumulation and distribution in Typha latifolia and Phragmites australis: implication for phytoremediation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(4), 3843–3852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-8135-6

Kovačević, M., Jovanović, Ž., Andrejić, G., Dželetović, Ž., & Rakić, T. 2020. Effects of high metal concentrations on antioxidative system in Phragmites australis grown in mine and flotation tailings ponds. Plant and Soil, 453, 297-312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04598-x

Mike, J., Gałczyńska, M., & Wróbel, J. 2020. The Importance of Biological and Ecological Properties of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud., in Phytoremendiation of Aquatic Ecosystems—The Review. Water, 12(6), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12061770

Montes-Rocha, J. A., Alonso-Castro, A. J., & Carranza-Álvarez, C. 2024. Mechanism of Heavy Metal-Induced Stress and Tolerance. In Aquatic Contamination (pp. 61–76). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119989318.ch4

Perna, S., AL-Qallaf, Z. A., & Mahmood, Q. 2023. Evaluation of Phragmites australis for Environmental Sustainability in Bahrain: Photosynthesis Pigments, Cd, Pb, Cu, and Zn Content Grown in Urban Wastes. Urban Science, 7(2), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020053

Rai, P.K. 2021. Heavy metals and arsenic phytoremediation potential of invasive alien wetland plants Phragmites karka and Arundo donax: Water-Energy-Food (W-E-F) Nexus linked sustainability implications. Bioresour. Technol. Rep, 15, 100741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2021.100741.

Rezania, S., Park, J., Rupani, P. F., Darajeh, N., Xu, X., & Shahrokhishahraki, R. 2019. Phytoremediation potential and control of Phragmites australis as a green phytomass: an overview. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 7428-7441.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04300-4

Sellal, A., Belattar, R., & Bouzidi, A. 2019. Trace elements removal ability and antioxidant activity of Phragmites australis (from Algeria). International journal of phytoremediation, 21(5), 456-460. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2018.1537252

Shen, X., Dai, M., Yang, J., Sun, L., Tan, X., Peng, C., Ali, I., & Naz, I. 2022. A critical review on the phytoremediation of heavy metals from environment: Performance and challenges. Chemosphere, 291, 132979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132979

Song, H. W., Sha, J. Q., Wei, S. H., & An, J. 2025. Low nitrogen MICP remediation of Pb contaminated water by multifunctional microbiome UN-1. Environmental Technology and Innovation, 38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2025.104097

Zamora-Ledezma, C., Negrete-Bolagay, D., Figueroa, F., Zamora-Ledezma, E., Ni, M., Alexis, F., & Guerrero, V. H. (2021). Heavy metal water pollution: A fresh look about hazards, novel and conventional remediation methods. In Environmental Technology and Innovation (Vol. 22). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101504

Zhang, N., Zhang, J., Li, Z., Chen, J., Zhang, Z., & Mu, C. 2018. Resistance strategies of Phragmites australis (common reed) to Pb pollution in flood and drought conditions. PeerJ, (1). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4188

Zhou, M., Yang, Y., Guo, Y., Chen, L., Li, Z., Liao, X., & Li, Y. 2025. Unraveling soil salinity on potentially toxic element accumulation in coastal Phragmites australis: A novel integration of multivariate and interpretable machine-learning models. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 217, 118072. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.118072